Direct link to story here

Q&A: Lt. Col. John Halliday (USAFR, Ret.) Author, Flying Through Midnight

Published on July 11, 2006 at

Direct link to story here

Candlestick C-123

Introduction

The sparsely-populated Asian nation of Laos is generally regarded to be the most-bombed nation on earth, having served as a second secret front of US involvement in the Vietnam War. Using its remote, difficult terrain as a political and military sanctuary, North Vietnamese forces massively infiltrated South Vietnam through Laos on the ‘Ho Chi Minh Trail,’ in reality a network of trails ranging in size from mere footpaths to roads wide enough for truck traffic. With both sides of the conflict actively fighting, and arming and supporting guerilla armies in ostensibly-neutral Laos, the nation quickly become a major focus of energy and strategy in the war.

Flying

a range of covert air support missions over Laos were CIA and US Air Force

special operations forces, flying from bases in neighboring countries such as

Thailand. One such task were “Candlestick” missions, illuminating

southward-traveling North Vietnamese night convoys with flares, so that other

strike aircraft could identify and destroy them.

Flying

a range of covert air support missions over Laos were CIA and US Air Force

special operations forces, flying from bases in neighboring countries such as

Thailand. One such task were “Candlestick” missions, illuminating

southward-traveling North Vietnamese night convoys with flares, so that other

strike aircraft could identify and destroy them.

Recently, a reader, Christian “Semmern” Semcesen, put us in contact with Lt. Col. John Halliday (USAFR (Ret.)), the author of “Flying Through Midnight,” a memoir of his war experiences flying Candlestick missions in a C-123K Provider for the 606th Special Operations Squadron. We had a chance to interview Lt. Col. Halliday about his training, the nature of his flying over Laos, and the tactics used by “Candlestick” crews.

Biographical information

Q. What first interested you in flying?

A. My parents said before I talked, when they’d drive by an airport, I’d point and exclaim, “Airp! Airp!” My Uncle George — a TWA captain — reinforced the attraction. I perched on dad’s shoulders outside the cyclone fence at Washington National when Uncle George taxied-in his Super Constellation, blasting propwash in my face. George deplaned wearing his gold-striped uniform and thunderbolts hat and gave me a wind-up Super Connie with spinner props that zipped across the living room. I was hooked.

Q. Why did you join the military?A. Growing up, I never saw myself as a military man. I’d graduated from the University of Miami in June 1966. Next, I attended night classes at George Washington University and carried enough credits to keep my draft deferment while I worked at the Department of Agriculture by day. The future looked bright, but then the roof caved in.

Out of nowhere, I got my draft notice in January 1967. The Selective Service cancelled my deferment. No explanation; they’d just cancelled it. If I didn’t join another service branch by the 31st, they’d grab me, likely stick an M-16 in my hands, and toss me into the jungles of Vietnam. I was in shock. That night, my dad and I watched body bags loaded onto planes in Saigon. The day’s Washington Post said the Air Force faced a pilot shortage. Dad told me that I faced the decision of my life. I could come home in a body bag, or try to become a pilot. But Air Force training meant six years. Or, I could roll the dice, try to survive Vietnam, and be out in two. On the other hand, my boyhood flying dreams might come true. Shoved from behind, I stumbled through the open door with a smile on my lips, determined to make the best of a bad situation. Little did I know, as Joseph Campbell wrote, “Being drafted was a death and rebirth.”

C-133

Q. What was your training prior to joining the 606th SOS?

A. The standard one year of Air Force pilot training, flying the T-37 and supersonic T-38. After graduation, they assigned me to fly the C-133 at Travis AFB, California. I attended three months of training at Dover AFB, Maryland. After eighteen months of flying the “Widow Maker” into Vietnam, they ordered me to Phan Rang, Vietnam to fly C-123K cargo missions. So I attended basic school in Columbus, Ohio, then tactical training at Hurlbert Field, Florida. There was no training to be a Candlestick pilot.

Q. How many hours in the C-123 had you logged before deploying to Southeast Asia?

A. Thirty at most.

Q. What was the allure of joining the unit for you?

A. I had no allure; I was clueless about the secret 606th SOS Candlestick mission. I’d just graduated from Jungle Survival School at Clark Air Base, Philippines. I was in the Clark terminal, ready to board a C-130 for Phan Rang, when they paged me. They’d changed my assignment. My next stop was a place called Nakhon Phanom, Thailand. I was thrilled; any place in Thailand was better than every place in Vietnam. So I bounced on springs across the tarmac to board a C-141 bound for Bangkok.

Q. Post-war, what was your military career?

A. They assigned me as a C-123K instructor at Columbus, Ohio, then Alexandria, Louisiana. I left active duty as soon as my six-year commitment was up to be an airline pilot. But no airlines were hiring, so like many pilots joined the Reserves to keep food on the table. Twenty years later, after flying the C-5 during the Gulf War, I retired as a Lieutenant Colonel.

Q. Post-military, what have you done prior to — and since — writing Flying Through Midnight?

A. I had a twenty-eight year airline career concurrent with my Reserve career. I flew B-767 transcons for my last ten years and retired from American Airlines last summer. Now I have a whole new career as an author.

Q. How long did it take to write, and why did you choose to write it when you did?

A. I thought I could knock it out in one year. It took three and consumed my life… still does. Why did I write it when I did? The secret war was still going on when I came home in 1971, so I was prohibited from talking. As years passed, the events quicksanded from memory. Then something happened in 1997. I don’t want to give away the end of the book, so let’s just say I wrote it to honor a pledge I made my father. My dad didn’t live to see the story published, but his photo sat perched at the back corner of my desk. Through all the setbacks, his smiling image encouraged, “I believe in you, Son. Keep going. You can do it.” I think the intimacy of the narrative sprang from dancing with my father again as I whispered my stories to him.

Navy P-2

A-26

Nakhon Phanom

Q. The covert air war over Laos was largely supported by a somewhat motley collection of WWII-era aircraft operating out of Nakhon Phanom RTAFB (NKP). Please describe the base itself, your living quarters, and ‘life at NKP.’

A. I’ll do better than describe; I’ll show. But NKP life was complex. I suggest reading the first chapter at FlyingThroughMidnight.com for the best answer.

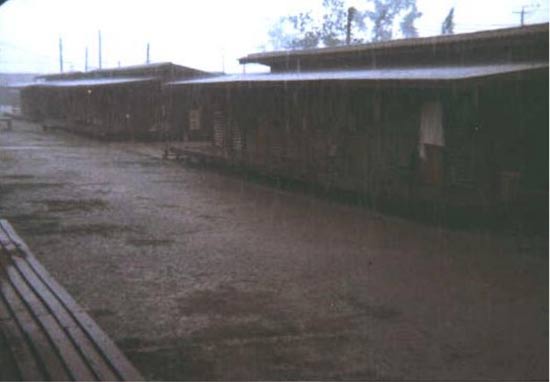

NKP final approach, the base carved from the jungle three years earlier.

Hand-drawn shuttle bus map.

A-1E Skyraider

Quarters (the dungeon) during Monsoon season.

Chow Hall (Penetrator Inn)

Q. What was your initial reaction to your deployment there?

A. I was thrilled at the prospect of flying cargo around Thailand. When I arrived at NKP, I was stunned to learn that the Candlesticks flew night combat missions, killing trucks charging down the Ho Chi Minh Trail under the cover of dark.

Q. The airbase itself is only a few dozen miles from the Mekong River, and the border with Laos. What was the threat environment like in the border area? Was there a general state of threat at the base, given the nature of what you were doing there?

A. Few know NKP was surrounded by a catacomb of tunnels the enemy used before the Air Force set up housekeeping. But we felt secure because of our air police, their dogs, guard towers, and a fenced topped by concertina wire. Yet the Candlesticks were like a secret society, so not even our air police were aware of our mission.

Karst

Q. What were the general flying conditions in and around NKP? Weather?

A. Except for the rainy season, the weather was excellent. Aside from dodging flak, the Laotian karst and jungle were our second-worst enemies. [F-105 pilot] Karl Richter bailed out in broad daylight into these razor-sharp mountains. Jolly Greens picked him up immediately, but he bled out en route. This is typical of the karst we were forced down in at midnight, dead behind enemy lines, blind and mapless.

Q. Some of the units flying from NKP flew in civilian clothes, flew unmarked aircraft, and so on…it must have seemed somewhat surreal flying for and with a force that was obviously American, but which was officially unknown. Or was that not the case?

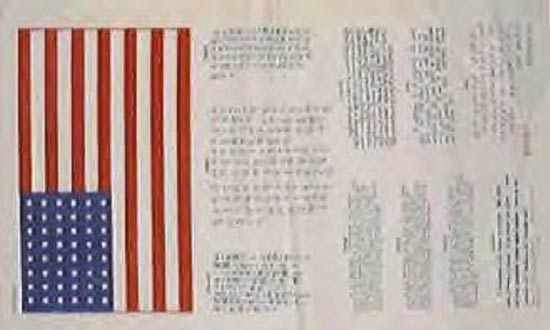

A. It was surreal. Candlestick crews flew in civilian clothes in the early days, then later in sanitized flight suits that were never going to fool the enemy. The sole item we were authorized to carry was this silk blood chit:

Blood chits featured our flag with an appeal in 14 languages: “I am a citizen of the United States of America. I do not speak your language. Misfortune forces me to seek your assistance in obtaining food, shelter, and protection. Please take me to someone who will provide for my safety and see that I am returned to my people. My government will reward you.”

Q. What was the general morale and mood of the men you flew with out of NKP?

A. We took care of each other. While some men were gung-ho, many were frightened and depressed. But rock ’n roll was our salvation. We were the Woodstock generation dragged off to war, so we duffle-bagged our music along for the trip. Rock was the oxygen tent that kept our souls from suffocating.

Q. Was there much intermingling, socially or professionally, of the crews flying the various types of aircraft out of NKP?

A. No. Each squadron stayed to themselves. But we did hang out with “Nail” forward air controllers doing the same job.

Q. Describe the bonding between your crew.

A. Blood brothers. After thirty-six years, our navigator Charles who saved my life that night called. He’d seen the book jacket and instantly knew it had to be our story of trying to land at Long Tien, Laos in pitch dark. We yakked for hours; it was as though no time had passed. I saved his life and he saved mine… a bond for life.

The C-123K

Q. How many combat hours or sorties did you log in the C-123K? Any other aircraft?

A. About seven hundred and fifty combat hours. We didn’t count sorties. I also logged combat time in the C-5 during Desert Shield and Desert Storm.

Q. The aircraft has somewhat of a reputation for being a rugged, versatile airframe. What were its strengths and weaknesses, especially as it related to your mission?

A. The C-123 saved my life, so I have nothing bad to say about that great warhorse. From Flying Through Midnight: “The C-123 has the heart and soul of a ‘Hog.’ If Harley-Davidson had built just one airplane, this would be it. Tough-looking. Durable. Raw power. Kick-ass reputation. A brawler that can take a beating and win. Works great with half the parts missing. Slow as hell off the line, but great top-end performance. A tank with wings. ‘Electra Glide in Black.’”

Q. If you could add one feature or capability to the aircraft, what would it be?

A. Easy: weather and terrain-mapping radar.

At War

Q. What percentage of your missions from NKP were ‘Candlestick’ missions?

A. One hundred per cent. We did nothing else.

Q. Tell us a little about a typical mission…did you have many specifically-tasked sorties, or was it more of an on-call, roving, ‘road recon’ type of task?

A. We prowled the Ho Chi Minh Trail for enemy trucks to bomb. As my sponsor Wiley explained, “When we spot a convoy, we drop three ground-burning markers off to one side of the road to mark the position. The jungle is so thick, the drivers can’t see them. Then we’ll set up a left-hand orbit over the target, call in fighters, and give them bombing instructions reference our ground marks. Then we sit back and watch the fighters blow the crap out of everything.”

Q. How were flares deployed? How many were carried? Was there a set number of flares dropped over a target? A procedure for how targets were illuminated?

A. Two loadmasters called “rampers” balanced on the knife-edge of our cargo door drawbridged open to the night sky deployed flares and marks via a home-built chute. And we carried both flares and ground marks. I don’t remember how many, but enough. We’d drop three flares to light a group of “good guys,” or three ground marks ahead of a convoy. We attacked one convoy at a time, but there might be twenty-five or fifty trucks.

Q. How were targets identified by your aircraft?

A. This once-top secret starlight scope that magnified moonlight a thousand times. Our scope navigator lay prone on an old mattress and peered out a three-foot-square hole in the cargo floor, using the scope to spot truck headlights.

Starlight scope

Q. What type of aircraft did you coordinate and work with while on station?

A. A C-130 command ship orbiting high overhead coordinated the air war. Their call sign in Flying Through Midnight is “Moonbeam.” When we’d spot a convoy, we radioed Moonbeam for fighters. Then a wide range of aircraft would show up: F-4s, A-4s, A-6s, A-1s…from all service branches.

Q. Describe both the AAA and the airborne threats Candlestick crew faced.

A. We dodged a thousand 37mm shells my first night out.

Three chapters tell about the night a MiG jumped us. We were outgunned, outperformed, and alone.

This Candlestick took a 57mm round in the vertical stabilizer. The crew thought they’d have to bail out over the Trail and become POWs, but though the tail section oil canned all the way back to NKP, the old Harley got them home.

The work was deadly. Getting rammed by a dive-bombing fighter ripping through our altitude was a constant threat. An RB-57 slammed right through one of our Candlesticks. Only the C-123 copilot survived.

Flak

Q. How were targets spotted, and what was the typical time period and procedure for calling in strikes?

A. With our starlight scope. But Laos is a big country. We needed help, so Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara created NKP’s Task Force Alpha (TFA).

Task Force Alpha (TFA)

Wiley explained, “Remember those huge electronic boards from the movie Dr. Strangelove that showed Russian bombers headed for the U.S.? Well, Task Force Alpha is like that but with real-time displays in living color, three stories tall . . . of trucks charging down the Trail.” So when we went hunting, we knew where to look. Fighters loitered nearby with KC-135 air tankers, so were minutes away.

Q. How long were your typical sorties?

A. About four hours over the Trail, then time from, and back to NKP.

Q. What was your normal operating altitude?

A. Ten to twelve thousand feet, unpressurized, slightly hypoxic.

Q. Describe the terrain that you were flying over, and how it helped and hurt your mission.

A. From the manuscript: “Northern Laos defies Darwin. The place is devolving to a more primitive state. There are Komodo Dragons and monitor lizards that can outrun a man and knock him down. Fifty-foot-long pythons that can swallow a man whole. Boas that can squeeze the breath out of a person and save the results for breakfast. Insects the size of your hand armed with inch-long scissor mandibles that can chew a finger off overnight. Really. I’m not kidding. Look them up yourself.”

Q. Talk if you would about the nature of flying over Laos in an undeclared, covert, supporting role to the fight over North Vietnam… were there special considerations that you planned for if downed?

A. The Air Force had no night rescue capability. No crewmember had survived a night bailout in northern Laos. They never made it to the Hanoi Hilton prison. They never lasted till morning. The key reason we carried a gun was to be able to commit suicide.

Q. What was the typical nights’ work? How many trucks or other vehicles would you encounter?

A. We expected to find at least one convoy. But some nights were quiet, like the night of November 6, 1970 when we were simply acting as a night light for a platoon of Lao good guys. But then all hell broke loose.

Q. What was your interaction with GCI while over Laos? How was your place in a nights’ sortie communicated to and from strike aircraft?

A. GCI interaction? None. We flew outside of radar contact, blacked out.

Our place in a strike? We’d spot trucks, then ask Moonbeam for fighters. If they figured our target was a priority, they’d order fighters loitering nearby. As the fighters raced in, we’d drop three ground marks in the jungle ahead of the lead truck, then set up a left-hand orbit so the scope nav could keep the convoy in sight. Once our fighters were six thousand feet above our position and could see our marks, I relayed bombing instructions: “The lead truck is two clicks west of my middle mark. Drop on a north-south run. I’m going ‘Christmas Tree’ (flicking my exterior lights on, then quickly off to avoid getting rammed, yet drawing a barrage of flak). If you have me in sight, you’re cleared in hot.

This wasn’t laser-guided bombing, so we added Kentucky windage till we hit the target. Simple, yet effective. Sadly, Laos today stands as the most-bombed country in history. Lao kids now use those bomb craters as swimming holes.

In the next photo, you’re looking straight down ten thousand feet through our scope hole at bomb craters. Notice no bombs hit the road.

Q. What was the most unique mission you flew?

A. The night of November 6, 1970 when we were forced down at midnight into that deadly karst, deep behind enemy lines, and were listed as Missing In Action — Presumed Dead. Our NKP comrades held our memorial service, knowing we were lost. But to paraphrase Will Rogers, rumors of our demise were greatly exaggerated.

Q. What happened on that mission?

A. We were flying deep behind enemy lines in northern Laos, flaring a platoon of Lao good guys being overrun by bad guys, awaiting for fighters to race in. The safety of the Mekong River was an hour south. NKP was yet another forty minutes south. Events seemed barely under control when disaster struck. We took a hit. A shell ripped open a main fuel line. Fuel gushed overboard. No way to stop it. Dry tanks in ten minutes. I could order a bailout and watch all seven men tortured to death by leftover bad guys we'd just bombed to hell, or slam headlong into a mountainside.

Just as I was about to order bailout, our nav Charles suggested I attempt to land at "impossible" Long Tien airstrip ten miles west. By today's standards, the approach would be like weaving a 747 through the canyon entrance to Yosemite Park guided solely by the light of a crescent moon that ducks behind an overcast at the worst moment, continuing by Braille — blind and mapless — then landing in the Lodge parking lot by the light of three 60-watt bulbs.

The book narrative puts readers in the left seat. They have all the information I had and can anticipate the decisions I had to make.

Q. Lt. Col Halliday, thanks for taking the time to tell us about your experiences.

A. John, thanks for a great interview. I’ve had a wonderful time.