July 25, 2021

We wake to the sad news that Snort died in a crash yesterday. I was honored to interview him in 2000, but it wasn’t our first encounter.

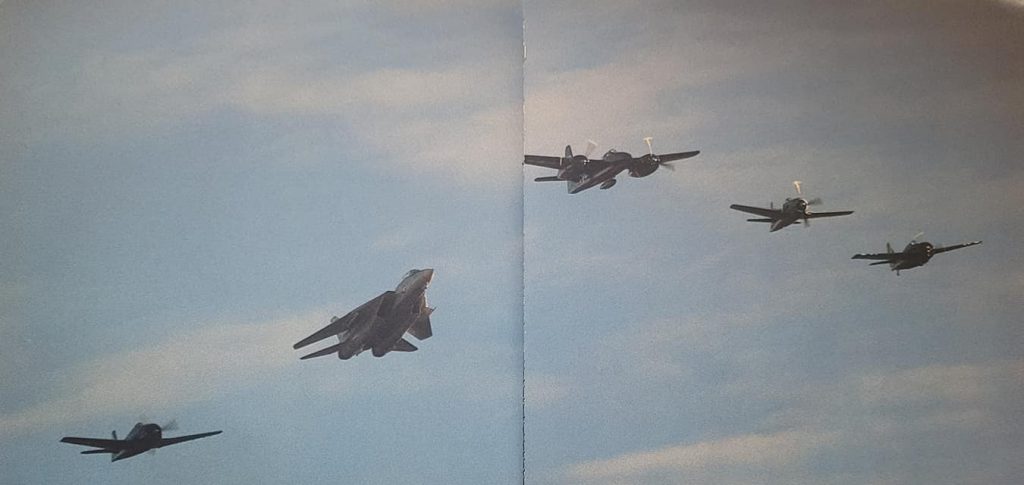

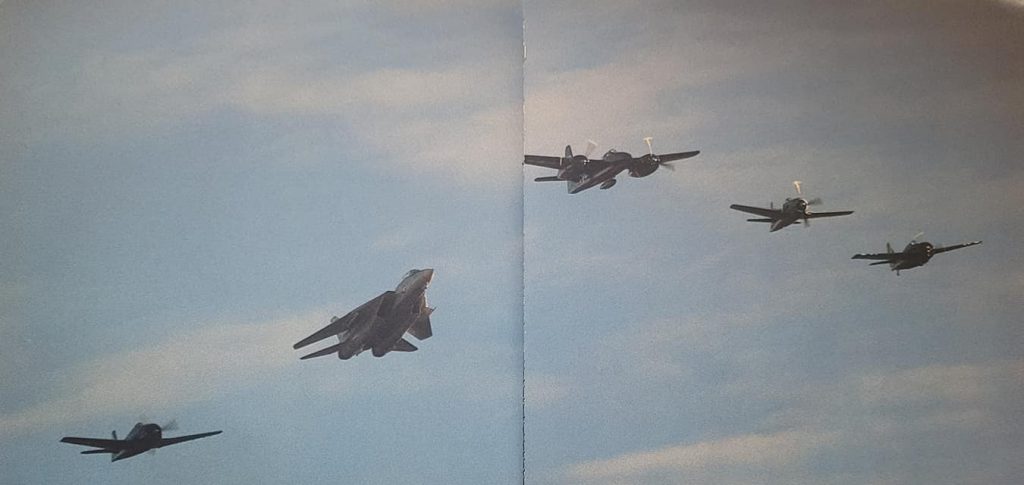

In 1985, I was there in the crowd as a teenager when he awed us all in the Tomcat at the Pratt & Whitney airshow in East Hartford. I have chills this morning thinking of the chills I had then, watching the Tomcat in formation with the other Grumman cats, and I do believe it was a missing man formation.

UPDATE: Video of the Missing Man, and an interview with Snort.

Photo from the official Pratt & Whitney commemorative book of the airshow.

RIP, Snort. Thank you for taking the phone call from a young writer with no credentials, but who was thrilled beyond words to interview the legend.

=========================

The Q&A has lived on the unformatted back pages of this site since I moved to the new platform. I have copied it below.

Q&A

Capt. Dale “Snort” Snodgrass (USN, Ret)

The F-14 and Naval Aviation

By John “Spoons” Sponauer

Originally Published August 30, 2000 by

All images below are thumbnails only.

“Cats” by C.S. Bailey

Image Courtesy of AviatorArt.com

If you’ve researched information on the F-14, it is pretty likely that the name Dale Snodgrass has appeared somewhere in what you’ve read. “Snort” is virtual legend in the Tomcat community, and with more than 4,800 hours in the F-14, he is the most experienced Tomcat pilot in the world. Over a 26-year career in Naval Aviation, he had moved from being the first student pilot to trap an F-14 on a carrier to commanding the US Navy’s entire fleet of Tomcats as the Commander of Fighter Wing Atlantic. Now retired, Snort is on the airshow circuit, flying a wide range of aircraft, from the F4U and P-51 to the F-86, MiG-15, and MiG-17.

The accolades for Snort’s flying are long and distinguished…..twelve operational Fighter Squadron / Wing tours, including command of Fighter Squadron 33 during Desert Storm, the Navy’s “Fighter Pilot of the Year” in 1985, Grumman Aerospace’s “Topcat of the Year” for 1986, a US Navy Tomcat Flight Demonstration Pilot from 1985-1997, and numerous decorations for combat and peacetime flight.

SimHQ.com recently had the honor and privilege to speak to one of the premiere naval aviators of his generation….Captain Dale “Snort” Snodgrass.

Dale “Snort” Snodgrass, at right in an F4U-5 Corsair

Photos used courtesy of Dale Snodgrass

BACKGROUND

First of all, thank you very much for talking with us tonight.

You grew up in Eastern Long Island, ironically near where F-14s were later made. How old were you when you first became interested in aviation?

My father was a Marine Aviator during WW II in the South Pacific and then a Test Pilot with Convair, Sperry Gyroscope, and finally Grumman, so my exposure and interest in aviation goes back as far as I can remember. I first flew with my father at around age 3 or 4. Growing up, I built every airplane plastic model that was available. WWI, WWII, jets, you name it and I had it. I remember that my father and I had a game that we played. When an airplane flew overheard, I would try to identify it without looking at it…..I got very good at recognizing the type of aircraft by the sound of its engine. However, it wasn’t until my junior year in college that I earned my private pilot’s license.

Did you consider other branches of the service besides the Navy?

Both my grandfather and father were Marines, so following the family tradition was a serious consideration, but my dream had always been to fly fighters off carriers. Becoming a Naval Aviator transitioned from a dream to a goal to reality!

I’ve read a couple of accounts of you doing some incredible flying, like doing a super-low departure from Rota, Spain that landed you in some hot water. And there is a famous shot of you flying past the USS America in 1989 that I understand is more of an optical illusion but still pretty seat of the pants flying. Is there some of that spirit in all fighter pilots?

YES, particularly in the good ones…a fighter pilot has to be aggressive. Aggression takes many forms, and one of the forms, especially for a new pilot just given control of an incredibly powerful aircraft, is to utilize that performance in some maybe-less-than-approved forums! Sometimes it’s not even showing off…you’ll do it even when there’s no one around, just because you can. I certainly had the propensity to push the limits and was occasionally reigned in by my superiors, but I always felt I had the maturity, acumen, and skill to fly and operate at the boundaries, be it aircraft performance or rules and procedures. Not to would be sacrilegious! When I became the CO of a squadron, there were a number of “non-warrior weasel paperwork-oriented weenies” who prophesized death and doom for both my squadron and myself. I told all my aircrew, “In this squadron only three things count: fighting Tomcats better than anyone else, landing on the carrier better than anyone else, and having the best maintained aircraft.” For guidance I said, “It’s very simple. I set the boundaries and you have to stay inside them. It’s very simple.”

End game…. we won every award available.

“The Shot,” USS America, 1988

Photo used courtesy of Dale Snodgrass

That shot off of the America is very widely used….most people seem to initially think it is either an edited photo, or a risky maneuver. What was it?

It’s not risky at all with practice…it was my opening pass to a Tomcat tactical demonstration at sea. I started from the starboard rear quarter of the ship, at or slightly below flight deck level. Airspeed was at about 250 knots with the wings swept forward. I selected afterburner at about 1/2 mile behind and the aircraft accelerated to about 325-330 knots. As I approached the ship, I rolled into an 85 degree angle of bank and did a 2-3 g turn, finishing about 10- 20 degrees off of the ship’s axis. It was a very dramatic and, in my opinion, a very cool way to start a carrier demo. The photo was taken by an Aviation Boson’s Mate who worked the flight deck on the USS America. Just as an aside…the individual with his arms behind his back is Admiral Jay Johnson, the immediate past Chief of Naval Operations for the Navy.

[CORRECTION PROVIDED BY READER D.M., who provided proof in July 2022 to me: “The famous knife-edge photo off the USS America is identified as being from 1989. It was actually taken July 22, 1988, during a practice run for CV-66’s Dependent’s Day cruise the following day. A short video of the famous banana pass was taken during the actual Dependent’s Day cruise, July 23, 1988.”] The year in the caption of the photo above has been changed to reflect this. Thank you, D.M.!!!!!

What was your most tense moment in the 26 years?

From a combat perspective, it was when I had a flameout over Iraq while executing a last ditch surface-to-air missile defense. I was leading a night Fighter Sweep in support of an A-6 strike on a power plant on the north side of Baghdad. My flight had flushed a couple MiG-29’s and we were in “Hot Pursuit.” My ECM and radar warning gear had been lit up like a X-Mas tree, so I was vigilant in jinking in altitude and heading, while rolling and visually checking for missile plumes. During one check, I saw a missile clearing the haze and undercast below us. We were 25-26 thousand feet at the time and the undercast was broken around 13-15 thousand. Net result…not a lot of time to see and react to a Mach 4 missile. Fortunately I was looking at the right piece of sky as the missile cleared the clouds. I immediately saw it had constant bearing and big time decreasing range. I immediately rolled the Tomcat into the missile and pulled 8-10 G’s while deploying chaff to aid in breaking the missile’s radar lock. The missile exploded just above and behind me. The missile defense worked as advertised (though it was really, really close). Unfortunately the F-14 has a tendency to depart controlled flight when a very hard rolling pull is executed at high subsonic airspeeds (I was at .95-.97 IMN). It is exasperated with external stores, and I had two external fuel tanks and six missiles loaded. I was able to recover the jet quickly, but in the process I lost my right engine. The recovery had cost me almost 15,000 feet and 300 knots. I was now slow with one engine thrustless and in the middle of all that pretty Triple-A gunfire that was shown on TV every night! I was too slow to get a good airstart attempt on the engine and didn’t want to go into full afterburner on the good engine, as the only fighters with one afterburner that could be airborne that night were Iraqi! With MiG’s in the area I didn’t want to be mistaken for TARGET!

I wound up going to min afterburner on the good engine, while descending deeper into Triple A “sparkles,” in order to get the requisite airflow to relight the engine. Once making heat and fire again, I climbed out with both engines in full afterburner. Though obviously tense, the previous event never seemed as tense as operating around the ship at night in bad weather as your fuel gage reaches low state, compounded by problems on the flight deck, and you being number 10 for recovery. Not to mention there is no divert airfield because the nearest land is 300 miles away!

One night, I was very low on fuel, the weather was terrible, and the deck was moving 15-20 feet. I was waved off twice because of a fouled deck…something that had nothing to do with me. I boltered (touched down just passed the wires) on my third try and went around for a fourth time. It was a really ugly pass…the deck was moving a lot and I was feeling more and more stress due to my rapidly dwindling fuel and no tanker available. I got it on deck with less than five minutes of fuel remaining. The thing is, though…almost every carrier pilot has a story like this. Ask any carrier aviator and they will tell you, life at the back end of the ship is one part thrill, one part chaos, and one part stress. Only the strong survive. It’s simply the toughest aviation environment in existence.

How about your most humorous moment? (this was answered by Capt. Snodgrass in a follow-up email to our conversation)

After thinking about that question, I found it revealing that I really couldn’t remember a really humorous flight. I know there were some exceedingly humorous exchanges on the radio, but they all fall into the “you had to be there” category. I guess it’s not a very funny profession when you’re flying in that serious of an environment. The “Laugh and Scratch” factor is rampant outside the mission, but the flying is exceptionally focused. I guess…be it combat, carrier operations, dogfight training, or airshow flying…the stakes are very personal and potentially fatal and thus very sobering. The bottom line is if you are not focused, your survival is at risk. End game, I honestly can’t recall a really funny flight. My log book is filled with phenomenal “I’d have to kill you to tell you” type of experiences, but imbedded humor is not a player. I have a thousand funny stories but I can’t remember any that really occurred in an airplane! They all involve people who fly and thrive around airplanes but involve events and conversations that occur while on terra firma!

However, this tale might work…I was an Ensign ( the lowest commissioned officer rank) and had just completed carrier qualification in the Tomcat…day and night. Being the first Ensign and the only one direct out of flight school to do that, I was rewarded with the privilege of picking up a brand new F-14 from the Grumman factory in Long Island, NY. My father was a VP with Grumman Flight Test and a long time test pilot. Being given the honor to pick up a pristine, brand new, world-beating fighter with my father delivering it to me was maybe the proudest and most cherished experience of my life…I don’t think I was ever more proud of him or he of me.

But that’s just the prelude…with me was a RIO (Radar Intercept Officer) who was also an Ensign. Grumman seized the publicity opportunity and while my father relished the moment, I focused on the flight back to NAS Miramar in San Diego. Not the weather nor the enroute support…but a fuel stop at Luke AFB outside Phoenix. It was during the ’73/’74 fuel crisis and Luke had refused transient fuel stops for over a year and a half. Literally days before my flight to Miramar, they had lifted the restriction. Prior to my touchdown, no F-14 had ever landed at Luke. I knew they were to receive the USAF’s first operational F-15 the day after our stop……the pot was too sweet to resist!

It was a short leg from Luke to Miramar so I knew I could request a unrestricted climb in full afterburner out of there…thus I timed my arrival for a late afternoon arrival and dusk take off (best light to see the 75 foot burner plume). The F-14 vs F-15 controversy was at its pinnacle, so the fuel stop was mandatory in my young parochial Navy Fighter Pilot eyes.

The real humor lies in how the USAF received me. As I taxied in I was directed to a parking spot directly in front of Base Operations normally reserved for Generals / High Ranking Officials. As we shut down the engines, a USAF sedan drove up and a Brigadier General popped out to meet us. I told my RIO to put on his cover (hat with our rank insignia) on as the canopy came up. Climbing down from the cockpit, I gave the General a proper salute but the expression on his face when he saw not one, but TWO Ensigns flying a brand new kick ass fighter that was head to head with the F-15…which no less than a Major had flown…was priceless. Never was I more proud to be a Naval Aviator!!!!!!!

As we departed with the sun setting in full afterburner, and most of the base watching, the departure controller witnessed our climb on radar with obvious amazement and asked us our type aircraft, as we were climbing through 20,000 feet and still over the runway. My RIO responded…..”We’re an Eagle Eater!” It was a good day to be an American!!!!

Of all the positions you held, which do you remember the most fondly?

Almost my entire career. Being a second cruise Lieutenant in my first squadron…I had been in the squadron for two years, and had gone to Top Gun. I was feeling very confident and enjoying what I was doing and gaining respect as a pilot and carrier aviator. Being an Adversary Instructor flying F-5s and A-4’s in VF-43 at Oceana…I was at the top of my dogfighting skills and was acknowledged by my peers as almost unbeatable. Plus I got to prove it every day. Being Commanding Officer of Fighter Squadron 33, particularly leading the squadron into combat in Iraq.

The most rewarding tour was my tour as Fighter Wing Commander. That satisfaction is from lots of things, but primarily from refocusing the community into precision attack. Namely, what I did to get the LANTIRN pod both proven as a system and funded by the Navy. Plus accomplishing that all in a year, unheard of in our current weapon system acquisition world. It really changed the whole respect for the F-14 community from being a fighter with zero support in the funding stream to being THE naval airplane that goes to the hard targets, and in reality turning the F-14 into a national asset.

As a humorous aside, are you aware of the Dale Snodgrass game that AT&T put on one of their pages about you?

http://att.com/mil/snort_history.html

(Laughs) Yeah, I know about it….they told me it was going online. I’ve checked it out a couple of times. It’s both humorous and flattering….

I like the animation of the eye winking.

Yeah, that really completes it.

TRAINING AND TOP GUN

You were the first Tomcat student pilot to trap the F-14 on a carrier, something only fleet crews were previously allowed to do. What can you remember about your first trap? Now, more than 1,200 traps later, what’s the single most important “trick of the trade” to get an aircraft aboard the ship?

your first trap? Now, more than 1,200 traps later, what’s the single most important “trick of the trade” to get an aircraft aboard the ship?

When the F-14 was introduced, the first crews to get it were those who had already made one cruise in F-4s or F-8s. They were proven. So yes, I was the first nugget to trap the Tomcat.

I don’t clearly remember the first daytime trap in the F-14, but I do remember the first night one. It was a whole new experience for me. I felt like I was a couple of seconds behind the airplane the whole way in. My first landing or two were not pretty and were not as elegant as I would have liked them to be, but I had no bolters. Most new pilots have a bolter or technique wave off their first couple of times out, so I guess in the big sense, I did OK.

The most important factors in trapping are concentration and just absolutely maintaining your scan, by which I mean keeping the airplane within its parameters, which are speed, angle of attack, and lineup. All of these come into play and are complicated by the others. As you adjust one, the others begin to deviate on you. Plus the condition of the sea and ship can play havoc with that, not to mention any kind of minor aircraft problems you are having.

You’re a 1976 graduate of the Navy’s Top Gun program. What did you learn there?

What Top Gun taught me was the ability to analyze and convey how to fight an airplane. It hones the flying and teaching skill sets that make you a valuable and competent air combat instructor. Top Gun was designed to take students and make them teachers in their own squadrons. The briefs were thoroughly done…every time you flew a 40 minute sortie, it becomes a 5-6 hour event with a very specific brief and debrief. In fact, the debrief alone can be as long as 2-3 hours, where every little thing you did is analyzed. You reconstruct every portion of the fight, and you look at the videotapes from each airplane and analyze each shot.

It’s a very thorough dissection….you talk about what’s going to happen, then you make it happen, and then you talk about what happened. You have to take the egos out of it so the learning is the focus, not who beat who.

I walked away from Top Gun a much more professional fighter pilot.

What are the most important traits for a fighter pilot to have?

Aggressiveness, and physically you have to have really good eyes. And by good eyes, it’s not so much physically seeing the other guy, but analyzing his energy state and knowing what he’s going to do. It all blends in the brain as you project a picture of what’s going down with micro second updates. The one who maintains the best situational awareness will, generally, be the victor. It’s almost a Zen art form.

How did your training prepare you for combat? In hindsight, what would have you wished you had learned in training that you didn’t?

Nothing…I felt really prepared and very confident. You really have to taste combat to understand it. The first time you experience it, and this has been true throughout history, you don’t how you’re going to handle it until you see and feel it. Confidence in yourself and your aircraft, and tested and honed with thorough training, are the critical elements of victory in air combat.

COMBAT OPERATIONS

You were in the air nearby when the two Libyan SU-22s were shot down over the Gulf of Sidra in 1981…in fact, you were supposed to be at that CAP station, but got delayed because of a tanker problem. What was the mood like on the ship and in the cockpits?

The day before the shootdown was the first day we had done our ops supporting the freedom of navigation [below the ‘Line of Death’]. Myself and the CO of VF-41 were the first ones out on patrol. I took it very seriously, but I also didn’t really expect as much to happen . As that first day wore on, the Libyans came out more and more and we got into more aggressive turning fights. The Rules of Engagement we were operating with forced us to wait for a hostile act, which meant a gun or missile being fired in your visual arena. The ROE sucked….we didn’t think it was any good, but we felt that at least we going to get up and finally see other fighters in the air. At the end of the first day’s debriefs, though, it was revealed to us from intelligence reports that in several cases, the Libyans were actually attempting to get into a firing position on us.

The next day was the shootdown. The Admiral personally briefed the ROE to me as I was walking to my Tomcat. I’m not sure everyone got that same attention. Shortly after reaching CAP Station Five, my section intercepted and engaged two MiG-25s in an aggressive 2 vs. 2 that lasted over four minutes. The shootdown at CAP Station Four occurred as we were going back to our CAP station after the MiGs had disengaged. To this day, I kick myself for not gunning the MiG-25 I had successfully positioned 800 feet at my 12 o’clock, with my pipper stabilized on the fuselage forward of those huge afterburners. Knowing that the MiGs would have fired if they had the shot, and I couldn’t until they did, was the stupidest ROE I could imagine. Fortunately, saner ROE was put in effect later.

Libyan MiG-25

Photo Credit: US Navy

Libyan Su-22

Photo Credit: US Navy

WAV audio file of 1989 F-14 Interception and Shootdown of Libyan MiG-23s

(File Size: 7.7 MB)

Original Source: US Navy

Ten years later, you led 34 strikes against Iraq during Desert Storm. Talk about what was going through your mind as you faced the Iraqis. How was it different than what you faced in Libya?

This was a completely different scenario…. This wasn’t a chess game, this was a war. We had strong Rules of Engagement here as well, but this time they were oriented on avoiding Blue on Blue engagements. From my perspective, Desert Storm was the main event that we’d been training for. Just prior to entering the Red Sea via the Suez all the Squadron CO’s sat down with the Battle Group Commander, and his opening comment was “OK boys, this is it….we’re going downtown.” With the potential Iraqi Order of Battle, we knew this could be a varsity event. The night before the war started, I gathered my 16 crews together and told them that this was the real thing and they had to remember everything we had learned and trained to, and all the things you have to live by: crew coordination, section integrity, etc. You have to execute the mission and not go off course chasing some MiG or something stupid. And I told them that in all probability, one, or maybe two, of our crews would be shot down before this thing was over. The war’s eventual outcome was inevitable and never really in doubt, but if the Iraqis had put up what they could have, my predictions might have been true. Desert Storm operations were very serious, even after the threat diminished. One of the ancient truths about combat is that in combat you don’t know what’s going to happen until it happens. In air combat, within the span of two seconds, things can get real ugly. You just have to take that deep breath and press on.

How would you compare the Libyans to the Iraqis in terms of pilot and tactics quality?

How would you compare the Libyans to the Iraqis in terms of pilot and tactics quality?

The potential strength and quality of both the Libyan and Iraqi fighter threat was substantial and real. However, in both encounters, their lack of training was evident, as well as the will to fight. From a fighter perspective, their demonstrated pilot skills were poor! Their tactics were very basic and in the Iraqi scenario almost always consisted of running away if they thought they were being targeted by a coalition fighter. I actually chased a MiG-29 200 miles at 1.5 IMN until I ran out of gas. As time marched on from 1981 to 1991, a ten year delta, the SAM quality and the ground control integration with their fighters improved, as did the quality of their aircraft. We were still flying the same F-14, which hadn’t really changed at all in that timeframe, but especially in Iraq, we were much better trained. The overall quality of the threat capability had improved, but their execution of that quality was still sub par. In fighter pilot terms they were “Grapes”… ripe for the plucking!

What types of threat aircraft have you encountered as a naval aviator?

I’ve never intercepted a Russian fighter, but in blue water ops, I’ve intercepted Tu-95 Bears, IL-38 Mays, M-4 Bisons….mostly long range platforms. The fighters that I’ve seen in potentially hostile situations are MiG-23s, Mirage III, and MiG-25s from Libya. On the Iraqi side, I never got to within visual distance, but I had MiG-29s on radar and run from me on three separate occasions.

What is the relationship between pilot and RIO…what kind of trust and respect do you have to have for each other? How do squadron mates relate to each other on matters of trust and character?

It’s a very tight bond/team. To maximize that within a squadron there is a Tactical Organization that is continually finessed. It normally matches up pilots and RIOs and promulgates who flies with who. That team is similar to a sports team….you attempt to match talent levels and personalities so that you have the best combo of fighting / training / survival abilities.

For example, a brand new pilot who checks in will likely be paired up with a seasoned RIO. Like any team, though, you are no stronger than your weakest link, so if you have a below-average RIO or pilot, that crew is not going to be as good a performer. You just try and balance the personalities and talent to derive the best possible fighting team possible.

In my case and at the more senior levels, I typically would fly with a senior talented RIO. The reason for this is that in that situation, I am, nine times out of ten, a strike leader and I don’t have time to have someone with me who needs “to be brought along.”

Looking back at the two-crew concept, when you fly with someone really good, you are much better off than you would be by yourself in any single seat aircraft. I had a couple of RIOs with whom it was as if we were glued together…our brains were connected. I’d suddenly be wondering what was behind us, and at the same exact time he’s calling out bandits in that direction.

THE F-14 AND OTHER FIGHTER AIRCRAFT

What are the biggest factors that separate the Tomcat from other fighters?

Aside from the obvious size and appearance differences, it’s easily separated from the F/A-18 and F-16 because, like the F-15, it was designed exclusively as an air superiority fighter. It has more loiter time, more range, etc. All of the peer planes are great airplanes and they’ve all done a great job, but the F-14 has been around longer than any of them. From a designer’s perspective, it’s the most archaic of the group, although it has design features that make it superior in many respects. From a flight control perspective, avionics, etc., it’s all 1960s technology, but it still probably has the longest range, is the fastest, and can carry the most ordnance of the whole group, save the F-15E.

It’s also the “trickiest” airplane to fly…it has the least pleasant flight controls of most modern jets. However, with its wings, flaps, etc. you can make it do things that the others just can’t.

Talk about the jump in capability when new engines and avionics were added to the F-14.

The GE engines certainly gave the airplane a lot of new life in the dogfight arena, and it brought it up to a level of thrust that the airframe was really designed for. The older engines were a result of politics and other factors, so the new engines made you feel like you were flying a rocketship!

The avionics upgrade was in the F-14D and that was a significant enhancement in air to air capability. However, the production was very limited. Over half the Tomcat community is still flying F-14A models.

The biggest capability upgrade was the LANTIRN pod and putting the aircraft into a world class precision strike role, and this all occurred at Naval Air Station Oceana while I was there. We deliberately kept the project away from Washington so they couldn’t get control of it. Martin Marietta, now Lockheed Martin, sent some reps up by invitation, gave us a LANTIRN pod to work with, and contributed some very smart people resources. I gathered some of my best people to work on the project, and in six months we went from an informal handshake to actually dropping laser-guided bombs from the F-14. I dropped a bomb from 18,000 ft and 22 miles away that blew the top off a tank at the Vieques range off of Puerto Rico. We made a short promotional video of those first bombs and then I went around to all the Navy Warfighting CINC’s in Europe and the Pacific and told them to let Washington know that they could have this capability on deploying carriers around the world in as little as six months, for no additional cost. It was a major jump in capability and in some ways we even exceeded the F-15E, which was designed for that role. One year after that concept discussion in my office, the LANTIRN capability deployed with VF-103 to the Med and Gulf.

F-14 LANTIRN Rollout – NAS Oceana, July 1996

Photo Credit: Lockheed Martin

F-14 with LANTIRN

Photo Credit: Lockheed Martin

One of the features that has always intrigued me is the Television Camera System (TCS) and the Infrared Search and Track (IRST). The F-14 is the only modern Western fighter to carry these sensors. How do you use them tactically?

TCS has been on the aircraft since it first came out. It is basically a 10x binocular that can be slaved to a radar lock. The TCS can give you a magnification, allowing you to get a visual ID on a target. In a predominately peacetime world and before newer ID systems, we lived with a Visual ID requirement. In other words, we had to have a visual ID before you could shoot. Even so, the TCS’s tactical application wound up not being significant in the fighter-on-fighter arena, but was a great aid on deployment when you were tasked to intercept and identify “unknowns,” which usually turned out to be airliners.

The IRST, only found on the F-14D, is more robust and it follows the trend of a lot of Russian systems. It’s totally passive; you can lock and track a target on IR signature alone at great ranges, based largely on his engine state. It brings that situational awareness much higher. Its shortcoming is that it doesn’t have great ranging capability.

Does it allow Non-Cooperative Target Identification?

The F-14D has a system of identifying targets with its sensors, but it isn’t tied into the IRST.

What do you think of the newer threat aircraft, such as the MiG-29 and Su-27?

From a flying quality, they’re very good. In some ways they’re better than, say, the F-14/15, and in some ways they’re not. All of these aircraft have basically equivalent performance. Until the production of these aircraft, I always felt that we had the performance advantage between our airplanes and theirs, and that is no longer the case. The things that make you win, though, are training and the ability to practice and fly like you fight. We have the ability to train to a level that no one else in the world can.

Any thoughts on the Super Hornet?

I think it’s a wonderful airplane, but you have to understand it’s a compromise design. It’s evolutionary, not revolutionary. From a flying quality standpoint, it has to be one the easiest planes in the world to fly. I could probably take a guy off the street and in 30 hours have him solo in the thing. It’s designed to be easy to fly because operating the complex radar and weapon systems is a huge challenge. From a tactical perspective, it was designed as a trash hauler…it wasn’t designed to be a “hypersonic cruiser” air superiority aircraft. There were a lot of politics at play in its development…the AFX was shot down, the Super Tomcat got shot down, and as a fall back they went with this robust improvement of the existing F/A-18. For the US Navy flying off a carrier with this airplane, it’s going to be the most reliable and safest airplane they’ve probably ever flown, and it will carry the “mail” for a long time.

FLIGHT SIMULATIONS

Have you tried any flight sims for the personal computer? Thoughts?

I have flown Microsoft’s Flight Simulator a bit. I’m not inherently a big-time computer guy, but the ones I enjoy the most are the WWII ones.

There hasn’t been an F-14 sim in a number of years and probably won’t be for a while. If you were going to help build one, what factors would be most important to you?

The most important thing would be making the flying quality as realistic as possible, specifically things like acceleration and pitch rates. Unfortunately, you can’t get the real feel of any airplane on the computer, but I’d want to get it as close as could be.

I’d also aim for ease of use, so it’s not too complicated. I have a couple of sims that I’ve received from companies and it’s just impossible for me to deal with them. I have to read the manual for three days just to figure it out.

Dale Snodgrass in the T-6 Texan

Photos Courtesy of Dale Snodgrass

AIR SHOWS

You’re an active air show performer, with more than 500 low level performances since 1987. You’ve also essentially qualified in every generation of aircraft since the 1940s, flying the F4U, P-51, F-86, Texan, MiG-15, MiG-17, and the F-14. If you could do it all over again, is there a certain era you would like to have flown in as a combat pilot?

Assuming I knew I would survive (laughs) I would say WWII would be the place, especially off an aircraft carrier. The next time period would be an F-86 pilot over Korea. So I’d say flying as a Hellcat pilot in the South Pacific or flying Sabres over Korea.

What traits does an air show performer need to have? How does it compare to naval aviation?

You need to be consistent and TRAIN. You must make sure that you fly by the numbers and you don’t change it, and you need to make sure you have the best equipment possible. You also have to realize that you’re not the same guy every day and you can’t let your ego or the crowd get in the way.

People make errors…the majority of airshow crashes are judgment errors, not something wrong with the airplane. And a sequence of errors may culminate in a catastrophic event. Like carrier aviation, it’s a very unforgiving business…you’re at very low altitudes and flying very aggressively. If you make an error, you have very little time to assess the error and react to it.

Captain Dale Snodgrass, thank you very much for taking the time to talk to us today.

My pleasure. Thank you.

Dale in the F4U-5 Corsair

Photo used courtesy of Dale Snodgrass

Copyright 2002 SimHQ.com. Reprinted with permission.

How would you compare the Libyans to the Iraqis in terms of pilot and tactics quality?

How would you compare the Libyans to the Iraqis in terms of pilot and tactics quality?